History

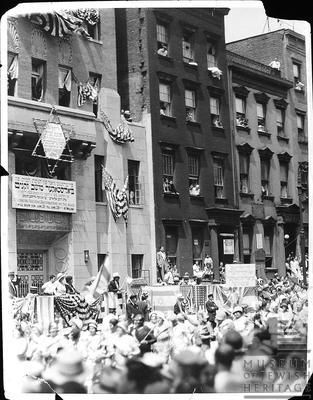

The New York Times issue of September 23, 1929, heralds the laying of the cornerstone of the Bialystoker Home for the Aged, which is preceded by a parade. The Jewish population of the district made the day a holiday and about 25,000 lined the streets to watch. Ralph Wein, head of the building committee, said “Too many Jews are spending their final years in city institutions and are pleading to be allowed to die among members of their own race.” In a type of philanthropy worthy of uptown wealthier residents, Bialystoker immigrants raised money with pushkas (little tin boxes) and other means so that its mutual aid society members could become “homeowners” by buying bricks for the building. Given the Depression’s hard times, they use long-term installment plans, so that poorer working families were able to contribute.

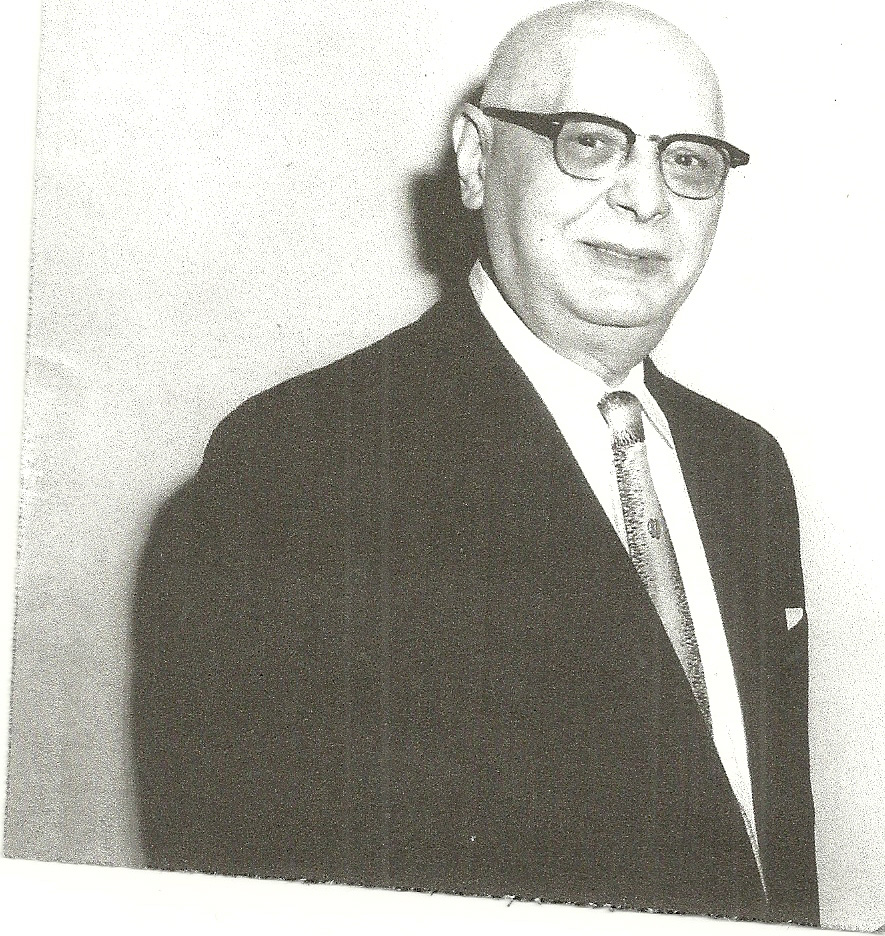

David Sohn, founder of the Bialystoker Center and Home

David Sohn, courtesy of Rona Moyer

The immigrant benevolent society Bialystok Bikur Cholim (sick benefit), erected the Bialystoker Center and Home to take care of the infirm and aged. Its building also served as the headquarters for Bialystok landsleit (people from the same town) scattered throughout the world. David Sohn was the driving force behind global philanthropic efforts and the establishment of the Lower East Side nursing home. He came to America in 1911 and became deeply immersed in Jewish communal life. In 1919, in the aftermath of World War One, Sohn founded the Bialystoker Relief Committee raising thousands of dollars to assist needy landsleit suffering as a result of the conflict between Russia and Poland. In 1926, the Committee – operating out of a cellar on East Broadway – under Sohn’s leadership launched the campaign to erect the Center and Home. He was actively involved in its management for the remainder of his life. David Sohn, who dedicated himself to public service, died in 1968 as a patient in the Home where his funeral was held. Members of his family have become actively involved in efforts to landmark the building.

Bialystoker Home

On June 21, 1931, the Home held an opening ceremony. According to a New York Times story, “Twenty-five years to the day after many of their number had fled from a pogrom in Bialystok, Poland, more than 5,000 Jews crowded East Broadway between Clinton and Montgomery Streets…and witnessed the opening and dedication of the $500,000 Bialystoker Home for the Aged.” President Franklin Delano Roosevelt and other elected officials sent congratulatory telegrams. Representative Samuel Dickstein pointed to the culmination of the drive as evidence that the Jews had always “taken care of their own people, without calling upon the government to find a place for the orphans and the aged.”

The home, which provided for 250 residents, contained an auditorium, dormitories, two synagogues, sun parlors and hospital wards. It later added assisted living options for elderly so that they could continue to socialize as part of the neighborhood’s fabric.

Opening June 1, 1931

Significance and Place in the Community

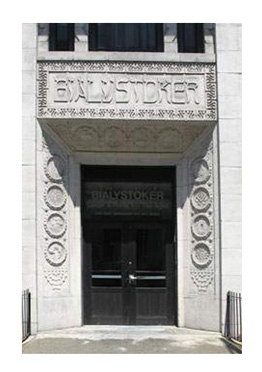

The Bialystoker Home reflects an important dialogue concerning tradition and modernity in immigrant life. Its Art Deco portal depicts Jewish symbols and proudly proclaims the word BIALYSTOK using Hebraicized lettering. Bialystoker’s immigrants serve as an early model for how today’s diverse transnational migrants broaden cultural and architectural traditions. We see how a traditional Jewish way of caring for the elderly (through a society called a Bikur Cholim) gets negotiated through this new building designed in an Art Deco style associated with progress.

The WPA Writer’s Project photographed and documented the Bialystoker Center for their famous 1939 NYC Guide. This modern facility for the elderly was opened by proud immigrants in a poor neighborhood who sacrificed to erect an imposing building offering the best of modern care. It is a type of philanthropy worthy of uptowners such as the justly famous Straus family who were among the founders of the nearby Educational Alliance. The Bialystoker’s response in facing the challenge of adjusting to a new life was to give generously to their community of origin while enriching their new city with a remarkable building. If it is torn down, we will lose a sense of the people whose stories it tells as well as those of an immigrant neighborhood whose best aspirations it represents. In keeping this building standing, its legacy can remain honored for future generations

Harry Hurwit, architect of the Center and Home

Harry Hurwit, 1955. Courtesy of Leah Fritz

Harry Hurwit was born in 1888 and grew up on the Lower East Side. As a boy, he enjoyed drawing. After working for some time in his family’s insurance business, Hurwit decided to enlist in the Army at the outbreak of World War One. He was among the first American soldiers to land in Europe where he fought in several major battles. While in France – to his great delight – he discovered Beaux-Arts architecture and, after returning home, enrolled at Cooper Union. After graduation, Hurwit set up his own firm where, for a period of 40 years, he received commissions for residential, institutional and commercial buildings. He is best known for his design of the Bialystoker Center and Home, which is listed on the National Register of Historic Places. Harry Hurwit never forgot his roots; he was a member of the Educational Alliance, the Grand Street Boys Association and the Veterans of Foreign Wars. He died on September 8, 1963. Several of his descendants have joined the campaign to save the Bialystoker Center and Home.

Closing of the Home Announced

The Bialystoker Home, one of the last major Jewish institutions operating on the Lower East Side, has closed and all residents have been placed elsewhere. The 10-story building, across East Broadway, that long housed The Forward, a daily Yiddish newspaper, is now a luxury condominium apartment building. Friends of the Bialystoker Home advocated for landmark status for the historic Art Deco building. We are pleased that the Landmarks Preservation has now designated the building as a Landmark.

Political Pressure

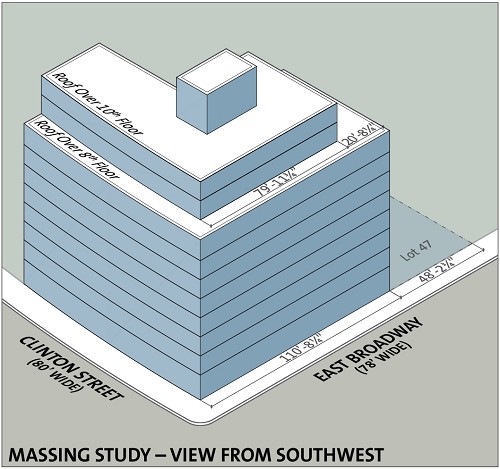

A Developer’s View after Demolition

Without landmarking, this might have been the fate of this beautiful building. The Board of the Bialystoker Home advertised the building for sale as “a highly desirable development site.”

Friends of the Bialystoker Home enlisted 16 Sponsoring Organizations and gathered hundreds of letters and petition signatures from concerned individuals, academics and citywide preservation, educational and cultural organizations to support landmark designation. After three extensive hearings, CB3 adopted a resolution in favor of landmarking. In May 2013, the Landmarks Preservation Commission designated the building as a Landmark.

Friends are grateful for the wonderful support provided by the sponsoring organizations and all those who signed petitions, wrote letters, and testified in favor of Landmarking. We are especially grateful for the steadfast support of Council Member Margaret Chin.

Read a Review of Rebecca Kobrin’s book: Jewish Bialystok and its Diaspora.